Astrognosia nova oder Ausführliche Beschreibung des ganzen Fixstern und Planeten Himmels samt einer gründlichen Anweisung, wie die meisten Seltenheiten, die darinne angetroffen werden, auf eine leichte Weise auszufinden sind….

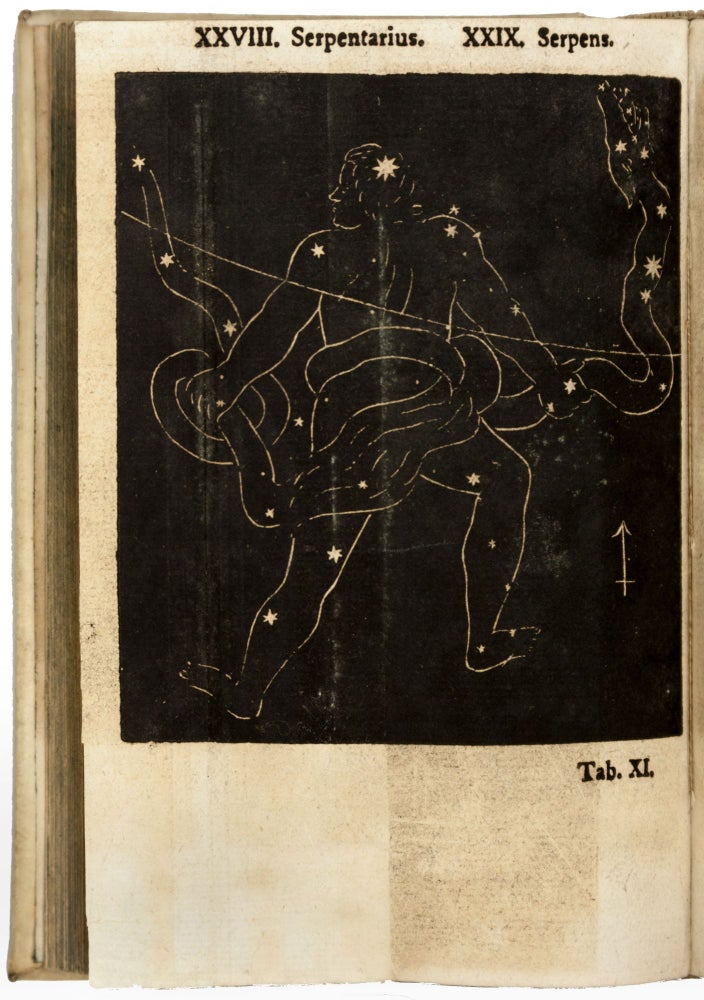

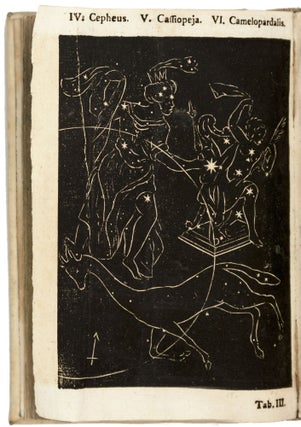

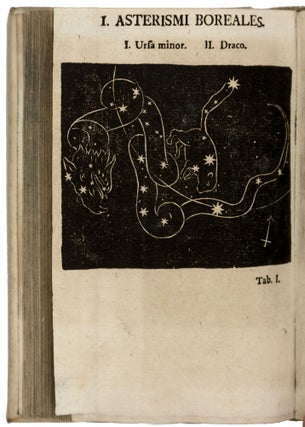

8vo., (11) ff., 260 pp., (7) ff. & 35 full-page & larger woodcuts of constellations, many folding. Bound in contemporary vellum.

[BOUND WITH:]

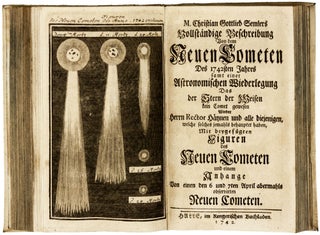

Vollständige Beschreibung von dem Neuen Kometen des 1742 sten Jahres samt einer Astronomischen Widerlegung das der Stern des Weisen kein Comet gewesen...Mit 1 gestoch. Tafel. Halle, Renger 1742. 8vo., (7)ff., 182 (ie. 152) pp. & 1 engraved full-page illustration of the comet of 1742. Rare first edition with text of this remarkably illustrated star atlas, the first to employ the woodcut to spectacular effect by showing white stars against a black background in representing the constellations. Most star atlases appearing before Semler’s work were by contrast engraved on copper, a medium not typically used to reproduce large areas of inky blackness to evoke the night sky and, moreover, were more expensive to produce than those with woodcuts. The 31 full-page woodcuts in Astrognosia nova first appeared without text in 1731 in a publication by Christian’s father, Christoph, entitled Coelum Stellatum. The present edition adds more than 260 pages of text on the history and practice of modern astronomy in German directed at students and amateurs. While the telescope had become increasingly available over the previous 100 years since Galileo, most stargazers (especially impecunious students) still made their observations with the naked eye. Semler acknowledges this reality by his evocative use of the woodcut medium and perhaps more directly with the following remark: "These [the stars] can be seen only with naked eye. With a telescope one sees so many that it is not possible to count them" [p. 101]. n Semler’s employment of the woodcut, images of the constellations are pictured by a thin white line circumscribing patterns of stars against a dense black background, conveying in a highly effective manner a close approximation of the way stars are visible as bursts of light against the night sky. Though similar to Bayer’s Uranometria (1603) with its use of mythological figures in outline to discriminate between the various constellations, Semler owes much to the more recent astronomy of Hevelius’ Firmamentum Sobiescianum, (1690). Given the effectiveness and visual impact of the woodcut illustrations in Astrognosia nova, it is curious how little this medium was employed: it first occurs in the Frankfurt edition of Galileo’s Sidereus Nuncius (1610) perhaps as an expedient to get the work out fast and cheaply. It was taken up again in mid-century by Giovanni Baptista Odierna and Geminiano Montanari, none of whose illustrations using the white on black woodcut style is as graphically ambitious as that found in the present work. Semler’s unusual illustrations received an interesting afterlife: “The copy of Semler’s atlas at the Library of Congress has the penciled notation: ‘Given to Whitney Warren [architect of the Grand Central Station] … 1913 and used in designing the ceiling of the New York Central Terminal.’” (See Warner, The Sky Explored, p. 238) The ceiling, decorated with constellations, still survives to this day. The Astrognosia nova is bound with Semler’s description of the comet of 1642 which he observed on April 6 and 7, accompanied by a full-page engraving of the comet. The work consists of two parts: in the first he gives details about the comet’s size, movements, and the possibility of its earlier and future appearances. The second part offers an astronomical explanation for rejecting the idea that the Star of Bethlehem was a comet. Semler’s controversial statement that possibly “on the surface of the comet’s crown there are sentient beings” (p. 15) was refuted in 1743 by the astronomer Johann Heyn in his Sendschreiben an den Magister Semler… Berlin 1743.

The core of Semler’s text consists of three parts: on the properties of stars; on asterisms; and “on extraordinary and mutable stars.” Interspersed throughout the book are various “Ausgaben” or astronomical problems for the students of astronomy (e. g. How to calculate the distance between Earth and the fixed stars? How to calculate the size of a comet?) and solutions or answers to these questions with examples. Typical of the more advanced textbooks of the period, the work presents the fundamentals of Copernican astronomy and refutes the system of Tycho Brahe. But he “goes beyond Copernicus by maintaining that there are an infinite number of stars, each the center of a planetary system. Within our solar system he explains what is known about the planets and then develops for each planet the astronomy that explains what its inhabitants would observe. He proves a priori and a posteriori that the planets are inhabited” (Schatzberg, p. 119). A son of a pietist clergyman and himself a preacher and astronomer, Semler tells the reader that “the number of stars is incomprehensible. And all have planets around them that cannot be without sentient beings, who praise their creator. Thus, from it we learn to observe His infinite glory and the significance of his providence, as he has to care for so many countless thousands of creatures” (p. 106).

* Poggendorff, Biographisch-literarisches Handwörterbuch zur Geschichte der exakten Wissenschaften, II, p. 902; Kenney, Catalogue of the Rare Astronomical Books in the San Diego State University Library, 174; Warner, The Sky Explored p. 248; Schatzberg, Scientific Themes In The Popular Literature And The Poetry Of The German Enlightenment, 1720-1760; Kronk, Meyer, Seargent, Cometography, vol.1: Ancient-1799; Bruening, Bibliographie der Kometen-Literature 1655. On Christoph Semler, see “Semler, Christoph,” in Klemme & Kuehn, eds., The Dictionary of Eighteenth-Century German Philosophers.

Sold