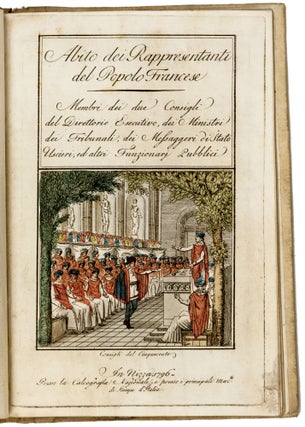

Abito dei Rappresentanti del Popolo Francese. Membri dei due Consigli del Direttorio Esecutivo, dei Ministri dei Tribunali, dei Messageri di Stato Uscieri, ed altri Funzionari pubblici.

Small 4to [20.5 x 13.3 cm], (1) f. hand-colored etched title page, 8 pp, 19 ff. full-page etchings in original hand-color. Bound in contemporary cartonato, later vellum spine lettered in ink, bookplate of Italian politician Alessandro Carlotti (1809-67) inside upper cover. Minor occasional toning and spotting, original hand-color still fresh and vibrant. Very rare first edition of this Italian-language costume book from post-Revolutionary France, published in Nice in 1796, the very year that armies under the command of Napoleon were invading Italy and while the Haitian Revolution was raging in France’s American colony of Saint-Domingue. The volume’s hand-colored etched title page and 19 full-page hand-colored etchings depict the newly proposed uniforms for French government officials and fonctionnaires operating under the recently established Directory of the First French Republic. The work is fascinating both as a record of the (uneasy) influence of Neoclassicism on male fashion, even at the highest governmental levels, and as a propagandistic document intended to pave the way for French influence on the Italian Peninsula and beyond. Especially interesting is plate 7, which depicts a government agent in charge of France’s overseas colonies in the Americas, who unconcernedly unfurls a large map depicting Saint-Domingue and confidently points to the island even as Toussaint Louverture was consolidating revolutionary control there. The 19-plate Abito dei Rappresentanti del Popolo Francese carries no information about authorship, either for its etchings or explanatory text, but the work is apparently related to Jacques Grasset de Saint-Saveur’s (1757-1810) 12-plate Costumes des représentans du peuple published in the same year (Paris, chez Deroy, 1796), given that their title pages and 8 of the plates are of similar design. Grasset de Saint-Saveur claimed that new costume styles were provided to him by “the Minister of the Interior.” These costumes are in the spirit of those famously sketched by the epoch-making Neoclassical artist Jacques-Louis David (1748-1824) in 1794 during Jacobin rule: “Although the idea of a civilian uniform was abandoned entirely after the fall of the Jacobins, the question of official uniforms to distinguish those people in authority was raised again by the government of the Directory shortly after the drawing up of the new Constitution in August 1795. Whoever was responsible for the designs for uniforms of Directory officials, given by the Minister of the Interior to Grasset S. Sauveur for publication in a volume of colored engravings with accompanying descriptions, owed more than a little to David’s proposals of a year earlier for his inspiration” (Harris, p. 308). The Abito dei Rappresentanti del Popolo Francese includes additional designs not present in the French-language work by Jacques Grasset de Saint-Saveur, including the Agent to French Colonies mentioned above. Christian-Marc Bosséno suggests that the Italian-language work was a baldly propagandistic project masquerading as a popular book on Neoclassical costume (“sous le prétexte de presenter au public éclairé ces costumes d’inspiration antique, mais en fait dans un strict but de propaganda,” p. 384). If so, its rarity today is perhaps partially attributable to the later rejection of French influence in Italy. Political import aside, the volume is a valuable witness to the influence of Greco-Roman dress on French fashion in the late 18th century. While neoclassical fashions for women were quickly and widely adopted, with radical new modes borrowed from ancient statuary, neoclassical styles for men proved more problematic. For example, long trousers and knee-length culottes, each with their own political connotations, were widespread and entrenched in France by the 1790s, but the use of trousers in antiquity always was associated with barbarians, with the toga or tunic being thought proper among Romans and Greeks. The fashions presented in the Abito dei Rappresentanti del Popolo Francese thus straddle the traditionally French and the modern-antique, both in form and coloration, e.g., the use of the Tricolore is prevalent (for both male and female revolutionary fashion see the excellent K. le Bourhis, et al., eds., The Age of Napoleon: Costume from Revolution to Empire, 1789-1815). OCLC locates U.S. examples of the Abito dei Rappresentanti del Popolo Francese at Brown and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. An alternate issue, unrepresented in U.S. collections, was published in the same year includes 7 addition unnumbered plates. A broadside showing all 19 costumes (extremely rare) was also produced by the same publisher of the Abito dei Rappresentanti del Popolo Francese and is illustrated in Bosséno (fig. 3, Raccolta Bertarelli, Milan). * K. le Bourhis, et al., eds., The Age of Napoleon: Costume from Revolution to Empire, 1789-1815; J. Harris, “The Red Cap of Liberty: A Study of Dress Worn by French Revolutionary Partisans 1789-1794,” Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 14, no. 3 (1981), pp. 283-312; C.-M. Bosséno, “La guerre des estampes: Circulation des images et des themes iconographiques dans l’Italie des années 1789-1799,” Mélanges de l’école française de Rome, vol. 102, no 2 (1990), pp. 367-400; Jacques Grasset de Saint-Saveur, Dresses of the Representatives of the People, Members of the two Councils, and of the Executive Directory… London, E. Harding, 1797.

Sold