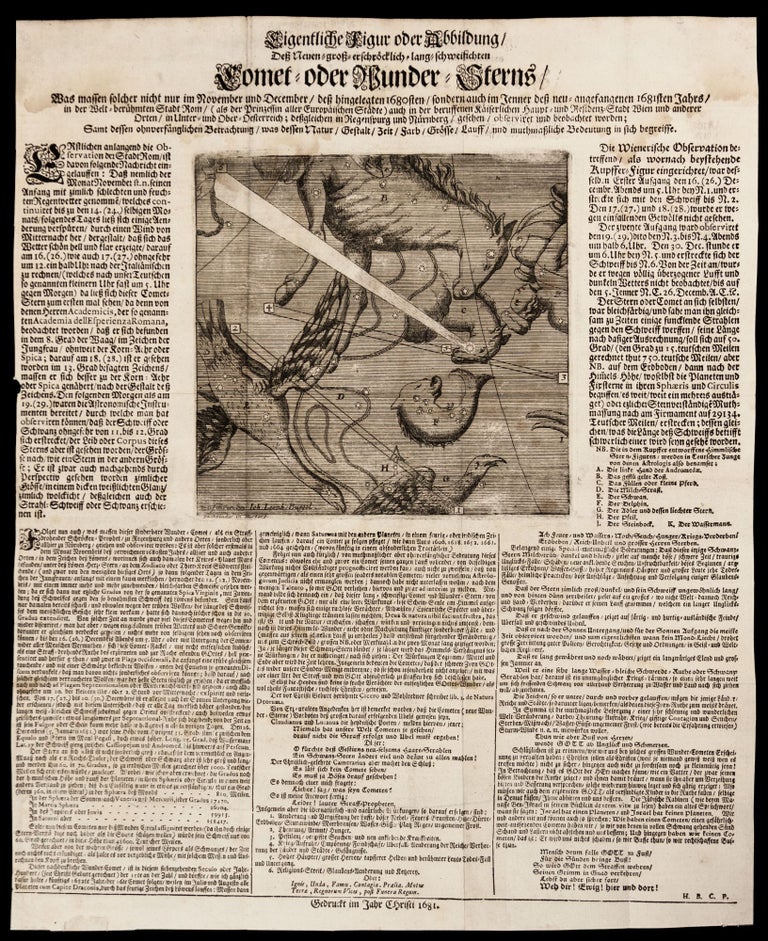

Eigentliche Figur oder Abbildung dess neuen gross erschröcklich lang schweifichten Comet- oder Wunder-Sterns ….

Folio sheet [48.8 x 37.3 cm the sheet; 19.1 x 18.5 cm the etching platemark], (1) f. letterpress broadside with etching. Unobtrusive creases from having once been folded (typical of such material), minor edge wear, unobtrusive pale damp staining. Rare illustrated broadside devoted to the Great Comet of 1680, later known as Newton’s Comet or Kirch’s Comet, one of the brightest comets ever recorded and the first to have been discovered through telescopic observation. At the center of the broadside is an etched celestial chart showing the shifting location of the comet in the night sky. Surrounding the etching is a detailed letterpress text discussing the comet’s “nature, form, duration, color, size, and course” as well as matters of prognostication associated with these celestial bodies. To the left of the etching is early observational data taken from reports coming out of Rome, and to the right is a report of observations made in Vienna. In three columns below the etching are local observations from Regensburg and Nuremberg, with notes on weather, the comet’s trajectory, its absolute magnitude and distance from earth, the ‘influences and meaning’ of the comet and its comparison to other comets. Gottfried Kirch (1639-1710), a former student of the polymath Erhard Weigel in Jena (1625-99) and an apprentice to Johannes Hevelius (1611-97) in Danzig, first observed the comet through his telescope in Coburg on the morning of 14 November 1680. The comet disappeared into the sun’s glare in early December, only to reemerge in late December having passed perihelion, at which point its tail grew to a spectacular 70-degrees in length. The present broadside notes that although the “star” itself appeared no larger than a “Reichs-Thaler” (the standard silver coin of the period), its tail was vast. Many observers took these two sightings to be two distinct comets, and only recourse to the most current theories of the New Astronomy would eventually disprove this: “The November comet was a morning object with a relatively modest tail, while the one in December was a bright evening object with an enormous tail. Not only did they appear physically dissimilar, but their apparent motions, when taken together, could not be represented with any figure resembling a circle or straight line” (D. K. Yeomans, p. 96). Georg Samuel Dörffel (1643-88), also a former student of Weigel in Jena, first recognized that the comet exhibited parabolic motion with the sun as its focus, a groundbreaking idea at the time which was quickly examined by Isaac Newton (1643-1727), Edmond Halley (1656-1742), and John Flamsteed (1646-1719), who exchanged letters on the matter. Flamsteed (wrongly) offered a theory for the unusual motion of the comet which combined solar magnetic attraction and repulsion with the effect of the Cartesian solar vortex. Newton, who observed the comet by telescope until 19 March, initially believed the November and December sightings to be two different objects, but eventually concluded that comets indeed travel in closed elliptical orbits, and he published these findings in the Principia (1687) with such a degree of accuracy that it has been posited that he used the newly invented calculus to supplement his trial-and-error calculations. “The triumph of Newton’s method for the unknown paths of comets was a significant step forward in the history of science,” and the firm mathematical foundation for all subsequent work on the dynamics of the heavenly bodies was thus established through Newton’s pondering of the Comet of 1680 (D. K. Yeomans, p. 104). Halley, seeing that Newton’s description of the 1680 comet might be applicable to other comets, wrote to Newton in April of 1687 a letter which would be prophetic of his future cometary fame: “Your method of determining the Orb of a Comet deserves to be practised upon more of them, as far as may ascertain whether any of those that have passed in former time, may have returned again” (see. D. K. Yeomans, p. 104). The present broadside, although written in the vernacular, is rather more sophisticated than its popular format suggests, being in fact a precise observational report of the comet written in the immediate aftermath of its appearance and incorporating information filtering in from Rome and Vienna, as well as data from the area around Nuremberg. The letterpress text of the broadside is signed “H. B. C. P.,” and in the plate the etching is signed “Zu finden bey Ioh: Leonh: Buggel Buchbinder in Nurberg [sic].” Buggel is recorded in a handful of other imprints from Nuremberg in the years around 1680 (though usually as a ‘bookseller’ rather than a ‘bookbinder’). While several sightings in German-speaking lands were recorded, only a few come from Nuremberg (see Bruning), and so a closer investigation into the astronomical personalities of that city might yet reveal the authorship (“H. B. C. P.”) of this broadside. OCLC and KVK locate no U. S. institutional examples of this broadside and only two outside of Germany (British Library and Zentralbibliothek Zurich). * V. F. Brüning, Bibliographie der Kometenliteratur, no. 1385; D. Y. Yeomans, Comets: A Chronological History of Observation, Science, Myth, and Folklore, pp. 95-109.

Sold