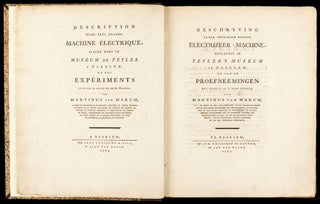

Description d’une très grande machine électrique, placée dans le Museum de Teyler a Haarlem / Beschryving eener ongemeen groote electrizeer-machine, geplast in Teyler’s Museum te Haarlem.

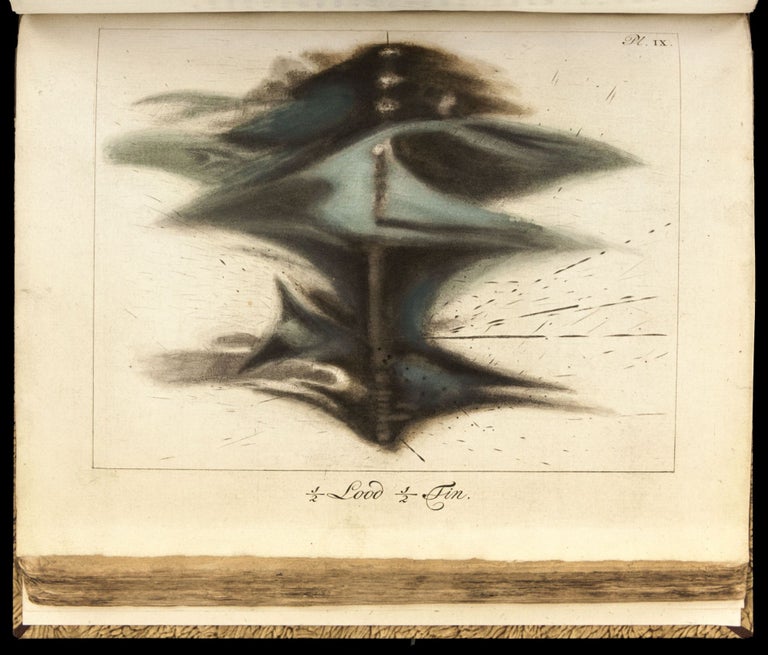

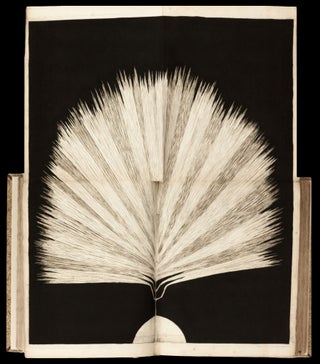

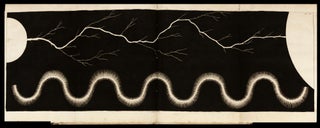

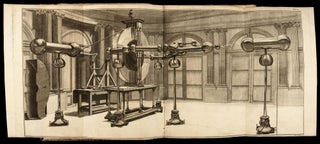

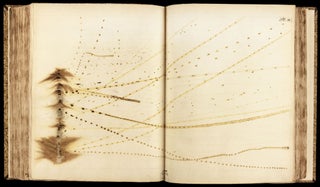

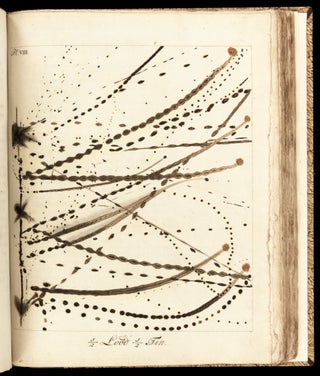

4to [27.1 x 22.5 cm], XXXI pp., (1) p. binder’s notes, 205 pp., (1) p. blank verso, with VI folding engravings. [Bound with:] Byvoegzel tot de Beschryving der Electrizeer-Machine, 11 pp., (1) p. binder’s notes, with I full-page engraving [Byvoegzel issued with 1787 Eerste vervolg but bound first here as called for in binder’s notes]. [And with:] Premiere Continuation des expériences faites par le moyen de la machine électrique tylerienne / Eerste vervolg der proefneemingen, gedaan met Teyler’s electrizeer-machine. Haarlem, J. Enschedé and J. van Walré 1787. XIX pp., (1) p. binder’s notes, 266 pp., with X full-page engravings (9 of which are in original hand-color). [And:] Seconde Continuation… / Tweede Vervolg… Haarlem, J. J. Beets, 1795. XV pp., (1) p. notes to binder, 391 pp., (1) p. blank verso, with VII engraved plates and III engraved plates (plates bound out of numerical order but as called for). [And:] MARUM, Martinus van. Déscription de quelques appareils chimiques nouveaux ou perfectionnés de la Fondations Teylerienne … / Beschryving van eenige nieuwe of verbeterde Chemische Werktuigen behoorende aan Teyler’s Stichting … Haarlem, J. J. Beets, 1798. VIII pp., 116 pp., VIII. 123 pp., XV folding engravings. Two volumes. Quarter bound in tan calf and patterned paper boards, morocco lettering pieces laid to spines. Bindings well preserved. Ownership inscription of the 19th-century scientist J. F. Plücker, several contemporary annotations, occasional pale marginal dampstaining, occasional very minor spotting and edge toning (not affecting images), minor wrinkling to some leaves in the second half of the Tweede Vervolg. Generally excellent. Rare first edition of the Dutch physicist Martin van Marum’s (1750-1837) spectacular foundational work in high-energy electrical research and a landmark in scientific illustration from an era in which experimental data increasingly took the form of fleeting, transient effects highly resistant to standard methods of artistic representation. Appearing just after the famous experiments of Benjamin Franklin and immediately preceding the most important work of Luigi Galvani and Alexander Volta, the copiously illustrated Beschryving eener ongemeen groote electrizeer-machine (1785-95) – here remarkably complete with its later supplements (as seldom found) – describes Van Marum’s ‘Large Electrostatic Generator,’ a room-sized device commissioned for Teyler’s Museum in Haarlem which was “the largest electrostatic machine ever built” until the rise of modern Van de Graf generators (Dibner, p. 295) and a machine which provided “the earliest demonstration of high-energy-density phenomena in the laboratory” (Larsen, p. 3). As director of the newly founded Tyler’s Museum, Van Marum at once set about transforming a ‘cabinet of curiosities’ established along early modern principles of collecting into a modern museum and cutting-edge research facility (the Beschryving thus can be read as a seminal text in the rise of modern scientific laboratories from the Wunderkammer tradition). Using bursts of electricity far more powerful than anything ever before achieved, Van Marum devised novel experiments to pursue chemical, magnetic and physiological researches, the most intriguing of which was the vaporizing of metal wires, a test of Antoine Lavoisier’s (1743-94) new theory of combustion (which at the time had not yet been published). These exploding-wire experiments generated spectacularly vibrant ‘abstract’ patterns on paper which Van Marum took great pains to have engraved and colored with the highest fidelity by the noted Amsterdam artist Jan Christiaan Sepp (1739-1811). The stark black-and-white plates of electrical discharges were engraved by C.H. Koning (with deep black backgrounds achieved by the hand application of printing ink). The result of this collaboration between scientist and artist was a work – published in only 300 copies and disseminated to scientific luminaries across Europe and America – which was unlike anything ever before achieved in printmaking. We can only imagine that Van Marum’s artist Sepp found the task artistically challenging in the extreme, being charged with inventing new techniques of engraving, painting, and workshop standardization for evanescent effects, all in the service of this new and mysterious science of electricity, which itself straddled the line between the visible and the invisible. Sepp had established his reputation as a peerless illustrator in his deluxe volumes on Dutch birds and insects (e.g., Nederlandsche vogelen [1770-] and Beschouwing der wonderen Gods [1762-]), but his assignment to illustrate vibrantly colored ‘abstract’ electro-chemical data – which to the modern eye looks to be a marriage of Rothko, Pollock and Frankenthaler – would be unlike any project he had before undertaken. In the present volumes Van Marum mentions Sepp’s contribution only as a footnote, but a letter he wrote to Sepp concerning these illustrations survives (Martinus van Marum: Life and Work, vol. VI, pp. 338-9) and reveals how exigent Van Marum was and adamant that Sepp and his workshop capture these ghostly designs with unerring precision and uniformity across all 300 copies of each experiment. While aspects of Van Marum’s experiments were published elsewhere in Italian, French and German, only H. C. W. Eschenbach’s German translation (Leipzig, Schwickert, 1788) dared to attempt reproductions of Sepp’s ineffable hand-colored engravings, a project that predictably achieved only mixed results and which would not have satisfied Van Marum’s insistence on fidelity to the “first originals,” but which nevertheless makes an instructive case in the perils of ‘translating’ at yet another remove images of such subtlety. “Van Marum’s experiments were greatly admired and repeated all over Europe. From his experiments with the large machine van Marum concluded that Franklin was correct in his theory of a single electrical fluid. For this support Franklin expressed his appreciation. Volta also greatly admired van Marum’s work, and informed him in 1792 of his own experiments; van Marum later introduced the term ‘Voltaic pile’ … In Paris in 1785 he met Lavoisier and saw his assistants at work. After his return home, he made his own experimental test [described in these volumes] and became convinced of the validity of Lavoisier’s combustion theory. He contributed greatly to the acceptance of the ‘new chemistry’ in the Netherlands by his Schets der leer van Lavosier (1787) [first printed in the present Eerste Vervolg at pp. 235-66]” (DSB). This succinct exposition of the whole of Lavoisier’s chemical system appeared two years before Lavoisier’s own account in the Traité élémentaire de chimie (Forbes, p. 188) and was the first coherent summary of this groundbreaking theory to be published. Teyler’s Museum, centered on the neoclassical Oval Room (1784), was built behind the house of Pieter Teyler van der Hulst, a wealthy cloth merchant and banker of Scottish descent, who donated his fortune for the advancement of art and science. Teyler directed that his ‘cabinet of curiosities’ and part of his fortune should be used to establish twin societies: Teyler’s First (Theological) Society (Teylers Eerste of Godgeleerd Genootschap), intended for the study of religion, and Teyler’s Second Society (Teylers Tweede Genootschap), which was devoted to physics, poetry, numismatics, history and art. Teyler’s Museum continued to house and collect artifacts of great variety (books, scientific instruments, fossils, minerals, drawings, etc.), but under the direction of Van Marum, who “rose to national fame by his energetic support of various attempts to replace the older contemplative forms of science by ‘new science’ based on observation and experiment plus measurement” (Martinus van Marum: Life and Work, vol. I, p. vii), the museum became an important institution for groundbreaking scientific experimentation. Teyler’s Museum retained its reputation for research well into the twentieth century. The theoretical physicist and Nobel Prize winner Hendrik Lorentz (1853-1928), for example, was Curator of Teyler’s Physics Cabinet at the height of his scientific career, from 1910 until his death, and supported scientific research in optics, electromagnetism, radio waves, and atom physics. Van Marum’s work on the Large Electrostatic Generator was published in the series of proceedings of Teylers Second Society (under the rubric Verhandelingen uitgegeeven door Teyler’s Tweede Genootschap), and the parts of the work sometimes can be found with the additional title pages of that series (parts 3, 4, and 9), although these series title pages are not called for by J. G. de Bruijn in his bibliography of Van Marum’s writings (nos. 10, 11 & 35). * Bierens de Haan 3070-3074; Wheeler Gift 532; Honeyman 2166; Mottelay, pp. 277-80; A. M. Muntendam, DSB IX.151-53; J. G. de Bruijn, “Van Marum Bibliography,” Martinus van Marum: Life and Work, E. Lefebvre and J. G. de Druijn, eds., pp. 287-360, nos. 10, 11, 35 & 40; E. Lefebvre and J. G. de Druijn, eds., Martinus van Marum: Life and Work, 6 volumes; Dibner, Early Electrical Machines, pp. 43ff.; G. l’E. Turner, “The Cabinet of Experimental Philosophy,” The Origins of Museums: The Cabinet of Curiosities in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Europe, O. Impey and A. MacGregor, eds., pp. 214-22; M. B. Schiffer, Draw the Lightening Down: Benjamin Franklin and Electrical Technology in the Age of Enlightenment; B. Dibner, “G. L. Turner and T. H. Levere, Martinus van Marum: Life and Work, Vol. 4” (book review), Technology and Culture, vol. 16, no. 2 (1975), pp. 295-6; J. Larsen, Foundations of High-Energy-Density Physics; W. D. Hackmann, “An Early Attempt to Oxidise Gold: Van Marum’s Large Electrostatic Generator and the Swan Song of Phlogiston,” Gold Bulletin, vol. 7, no. 3 (1974), pp. 80-83. Letter from Van Marum to Sepp in Martinus van Marum: Life and Work, vol. 6, pp. 338-39.

Sold