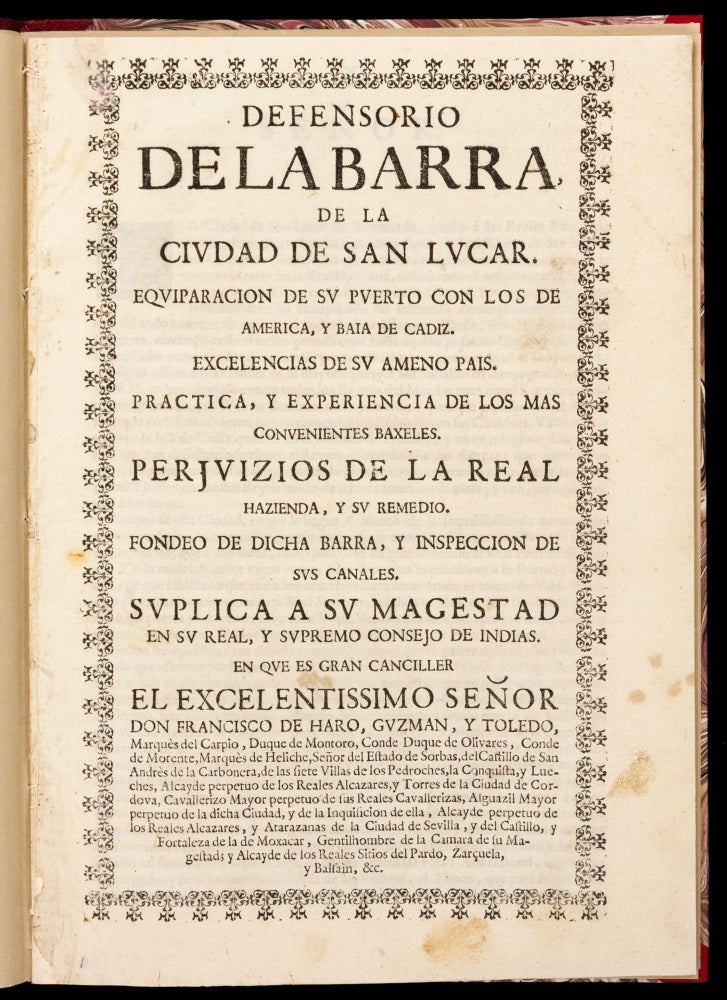

Defensorio de la barra, de la ciudad de San Lucar. Equiparacion de su Puerto con los de America, y baia de Cadiz.

Folio [28.7 x 20.0 cm], (1) f. title, 16 ff. Quarter bound in modern morocco and marbled boards. Binding well preserved. Minor marginal staining to title, otherwise remarkably fresh and well preserved. Very rare first and only edition of an official document rich in first-hand information about Spain’s 17th-century trade with its American colonies and the tense contest between Spanish cities to control this invaluable Americas monopoly, including many details concerning ports, ships, captains, and conflicts, from Florida, to Puerto Rico, to Cuba and indeed across Spain’s full circuit of maritime commerce throughout the Spanish Main and as far south as Argentina. This collectively authored appeal was addressed to the Consejo de las Indias by prominent officials from Sanlúcar de Barrameda, the port city of Seville, as a vigorous defense of their longstanding position as the sole entry and exit point for Spain’s transatlantic trade with the New World. By the turn of the 18th-century, Seville – a victim of geographical realities, political machinations, and even new trends in shipbuilding – had been forced to cede some of its privileges to the nearby port of Cadiz. The Defensorio de la barra de la ciudad de San Lucar was drafted as lobbying effort intended to arrest and reverse these changes by examining (and refuting) the arguments commonly made against the Sanlúcar/Seville port. The work provides an extended comparison of Sanlúcar’s port and personnel to those of Cadiz and to the numerous American locales where treasure ships arriving from Spain put down anchor on their annual voyages to the colonies. While the Defensorio certainly paints a vivid picture of this important contest between Seville and Cadiz (still very much in the balance at the time of writing), the value of the document today lies more in its dense skein of information about maritime culture in American waters during the second half of the 17th century. As a document written by government officials for government officials and never intended for a general readership, the Defensorio quickly (and obliquely) cites hundreds of recent incidents and anecdotes to support its points. These incidents at the time were readily familiar to those consulting the document (being daily involved in transatlantic trade) but are likely today to present new information to historians. Sanlúcar de Barrameda, located at the mouth of the Guadalquivir River, was long considered a perilous port because of its shifting sandbar, which could be crossed only with the aid of skilled local pilots under certain tidal conditions and could not be traversed at all by vessels of too great a tonnage. This geographical shortcoming was exacerbated by a shipbuilding trend from about 1650 which saw an expansion of the construction of massive galleons over the more modestly sized vessels which hitherto had anchored at Sanlúcar (or even sailed up the Guadalquivir and directly into Seville). Such technological changes thus seemingly favored the open harbor of Cadiz, where goods aboard large galleons could be safely unloaded in a deeper port without first having to be transferred to smaller barges (a necessity at Seville). The authors of the Defensorio, however, insist that Sanlúcar’s port was not as dangerous as had been claimed (its human and material infrastructure had been honed over centuries), and they point out the equivalent or greater perils faced by Spanish treasure fleets when visiting ports both at Cadiz and in America: The accommodating port at Cadiz lay open to enemy attack (recent history had proven this), and American’s easily navigable ports were also prey for pirates (evidence for this was abundant), while America’s hard-to-navigate ports were often more perilous to anchor in than Sanlúcar had ever been (as evinced by the recent record of American shipwrecks). Furthermore, the new massive galleons, the writers claim, were too unwieldy to steer surely or to defend themselves adequately against attack, and thus more goods were lost foundering at port in America and to piracy across the Spanish Main than ever were lost on the sandbar at Sanlúcar (which boasted an unblemished record of dissuading raiders from sailing up the Guadalquivir against Seville). These arguments, in retrospect, seemingly did little to help Seville fend off Cadiz as Spain’s American port (the Casa de Contratación was at last transferred from Seville to Cadiz in 1717), but the points made in the Defensorio could prove to be a boon to modern historians. Anecdotes specifically relating to American waters are too numerous to cite in full here, but topics treated include the especially dangerous geography of ports at Havana, Veracruz, Cartagena and Portobello (with info on recent shipwrecks; 3v), the unsuitability of galleons in defending themselves against American piracy (with dozens of examples naming locations, ships, captains, attackers, and contours of engagements, such as raids by the pirate Laurens de Graf [1653-1704; “Corsario Lorençillo”; 6v & 9v] on Veracruz and by the ‘Greek’ pirate Giorgo Nicolò [“un Griego llamado Jorge”; 8r] at Campeche), the use of pilots in Florida by a certain Capitan Antonio Garcia (de Mendoza?; 7v), the recent published opinions on American trade by the most expert navigators (e.g., the “cosmografo mayor Joseph de Beetia” [i.e., Veitia Linage]; 3r), the routes of mercury shipments (12 r-v), the slave trade (including ships “para Guinea à llevar Negros à Indias” [1v] and ships involved in asiento ventures [“Naos del Asiento de los Negros”; 6v]), and the names of scores of ships and their captains (with info on ship sizes, cargo and values), which sailed to Havana, Santo Domingo, Veracruz, Cartagena, Maracayo, Caracas, Tabasco, Cumaná, Buenos Aires, etc., etc., all of which collectively forms a vivid account of the in-the-water realities of the American commerce at the time. The final leaf of the Defensorio lists the dozens of members of Sanlúcar’s ‘Cabildo, Justicia, y Regimiento’ who supported the document, as well as the names of those who signed and certified the original manuscript for submission to the Consejo de las Indias on 17 December 1701. The Defensorio would then have been printed shortly thereafter in a limited number of copies for immediate distribution to relevant officials. OCLC and KVK today locate only 2 worldwide examples of this very rare work (Biblioteca Nacional de Chile and Universidad de Sevilla). * F. Aguilar Piñal, Bibliografía des autores españoles del siglo XVIII, vol. 9, p. 203, no. 1552; A. Girard, Le Commerce français à Seville et Cadix an Temps des Habsbourg; B. Moses, Casa de Contratacion of Seville; P. O’Flanagan, Port Cities of Atlantic Iberia, c. 1500-1900.

Sold