Observations relatives à la santé des animaux, ou Essai sur leurs maladies.

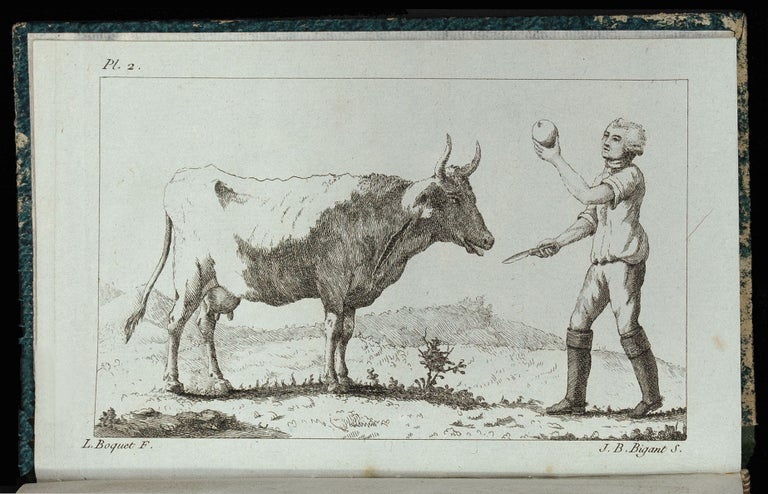

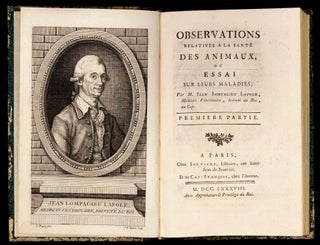

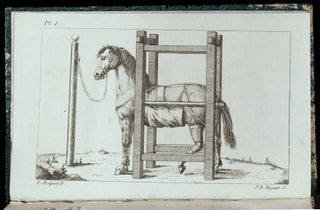

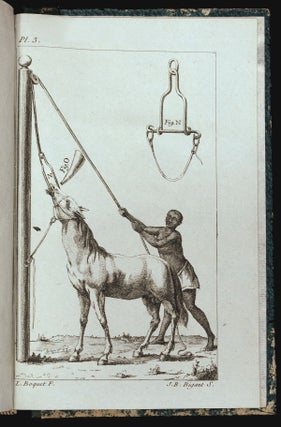

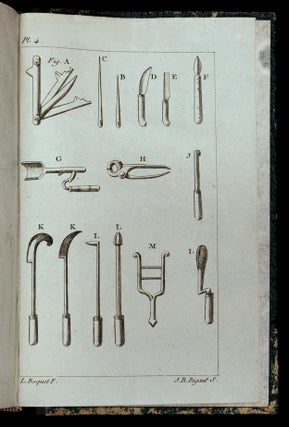

8vo [19.2 x 12.0 cm], xiii pp., (3) pp., 330 pp., 4 full-page engraved plates and with (1) full-page engraved author portrait, woodcut headpieces and tailpieces. Quarter bound in contemporary green morocco and green painted boards, spine richly gold tooled, yellow edges, modern bookplate inside upper cover. Some rubbing and edge wear to covers. Occasional very minor spotting and staining, marginal paper flaw at p. 113. Rare first edition of an illustrated work documenting the introduction of professional veterinary medicine into Saint-Domingue in 1770s and 1780s, with eyewitness information not only on the establishment of modern scientific procedures there, but also on slaves, slavery and the tense socio-political climate then prevalent in the colony. Published in 1788, on the eve of the French and Haitian Revolutions, the Observations relatives à la santé des animaux is the work of the marechal Jean Lompagieu Lapole, who arrived in Saint-Domingue in 1777, setting up a practice in Cap-François (today Cap-Haïtien) specializing in the care of horses. The low survival rate of Lapole’s book – which was available for sale both in Paris and ‘chez l’Auteur’ in Cap-François – can be attributed not only to the work’s nature as a practical manual (and the proximity of its publication to these revolutionary upheavals), but also to its controversial content: Railliet & Moulé claim that, “The first edition, which contained indiscretions about the treatment of blacks, was largely destroyed by the colonists” (p. 603). Lapole’s stated scientific aim is both to survey animal diseases peculiar to the West Indies (he notes that “the illnesses in Saint-Domingue differ almost completely from those in Europe” [p. 304]) and to offer Enlightenment suggestions about epizootic causes and prevention, quarantine, breeding, pasturage, problems posed by native plants (e.g., manioc, bananas, p. 61), and the like. His book, however, is as much a memoir as it is a technical manual, and he states that the volume, “should be considered less a treatise than a true account of my handling of veterinary maladies in this Colony” (p. 1). Lapole thus records numerous anecdotes of more-than-veterinary interest. He discusses, for example, the extreme paranoia of colonists, who (recalling, no doubt, the poisoning sabotage perpetuated by the notorious slave François Mackandal in 1758) tended to attribute every animal epidemic to poisoning by slaves, resulting in a vicious cycle of unjust “suspicion, arrest, and conviction” (p. 7); he recounts a case of suspected animal poisoning by a slave and the related experiment he conducted to prove the man’s innocence (by systematically dosing a healthy animal with the claimed ‘poison’ to no effect; pp. 283-91); Lapole laments the inefficacy of the traditional animal-healing methods practiced by slaves (pp. 30-33) and the tendency of slaves to drive horses and mules too hard and to abuse them in operation of the sugarcane mills (pp. 53-6); and he notes, generally, the inescapable reality of human abuse begetting animal abuse, of mutual suspicion between master and slave, of the rage of Africans at their enslavement, and how such an environment is both harmful to animals and resistant to the efforts of one such as himself who is committed to a “career of observation” in scientific veterinary medicine (e.g., pp. 7-11, 34-9, 64-77; on the metaphor of slaves-as-livestock in 18th-century Saint-Domingue, see K. K. Weaver, pp. 76-97). Lapole also offers a warning about the geopolitical implications of this dysfunctional environment, remarking, for example, that horse breeding in Saint-Domingue remains in a dire state, and that if Great Britain and Spain should ally themselves in war against France (as is rumored), France would need to rely too heavily on the United Stated for the military procurement of these animals (“How embarrassing!,” Lapole remarks; pp. 92-3). Lapole addresses his Observations to the French École Royale Vétérinaire d’Alfort, founded in 1765 by Claude Bourgelat (1712-79), who in 1762 established in Lyon the world’s first veterinary school. Lapole’s work therefore can be seen not only as an early work of professional veterinary science in the Americas, but also as an early professional veterinary work of any sort (see Railliet & Moulé on the Alfort school). Lapole gives much information about fellow veterinarians from the first generation of the discipline working in Saint-Domingue and provides excerpts of the numerous veterinary notices he published in the Port-au-Prince newspaper, Affiches Américaines, and in the various transactions of the Cercle des Philadelpes in Cap-François, the colony’s influential academic society (1784-1791) (these publications rank among the incunables of Saint-Domingue printing; see McClellan, pp. 181 ff., and L’Imprimerie hors l’Europe, pp. 35-5, 144). Lapole’s careful inclusion of this material, as well as his inclusion of a full-page portrait of himself, perhaps points to a certain professional anxiety: Although he allies himself with the Alfort school, he was not in fact a graduate, but practiced veterinary medicine under a royal license (‘brévéte du Roi’). In the second half of the volume, Lapole catalogues the most common (generally equine) diseases encountered in Saint-Domingue, including impetigo, glanders, respiratory illnesses, lymphatic tumors, anthrax, arterial worms (he touts his discovery of this ailment in 1780) and gives the topic a full treatment, ‘spasms,’ laminitis, bone diseases, fistulous withers, skin diseases, rabies, etc., along with suggested remedies, some of which utilize American plants (e.g., tobacco). This catalogue is supplemented with 4 full-page engravings (designed by L. Bignant and engraved by Jean-Baptiste Boquet) which depict specialized surgical instruments Lapole used in Saint-Domingue, a purpose-built stall to aid in healing equine fractures, a bull being operated on to remove arterial worms, and a harness for force-feeding horses and mules (here operated by an African slave in a loincloth). OCLC locates only 2 U.S. institutional examples of this 1788 first edition (National Library of Medicine and Harvard Medical). In 1791, still residing in Cap-François on the eve of the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804), Lapole published a slightly updated second edition under the title Observations relatives à la santé des animaux de St. Domingue (OCLC locates no U.S. copies of the 1791 edition). * Mennessier de la Lance, Essai de bibliographie hippique, vol. 2, p. 120; Guerra, F., Bibliographie médicale des Antilles Françaises, 72; K. K. Weaver, “Makandal and the Medical Care of Animals: The Veterinarians Who Inspired the Haitian Revolution,” in Medical Revolutionaries: The Enslaved Healers of Eighteenth-Century, pp. 76-97; J. E. McClellan, Colonialism & Science: Saint Domingue in the Old Regime; A. Railliet & L. Moulé, Histoire de l’École d’Alfort.

Sold