Extirpacion de la Idolatria del Piru. Dirigido al Rey N.S. en su Real Conseio de Indias.

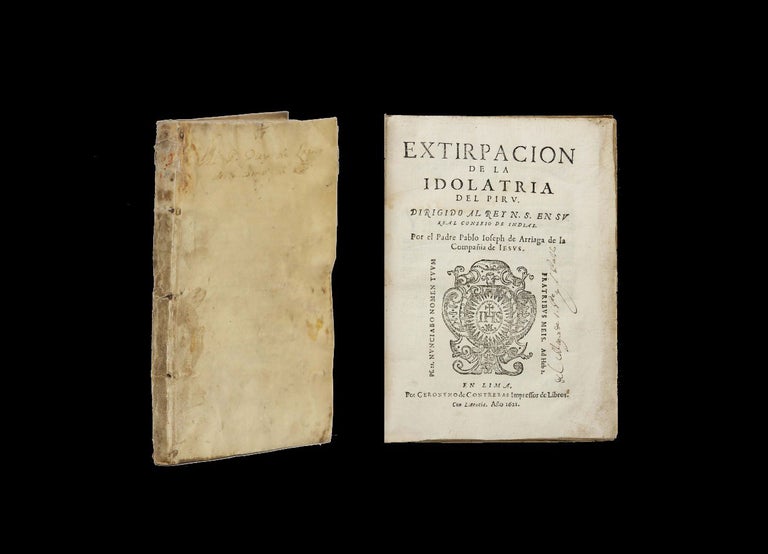

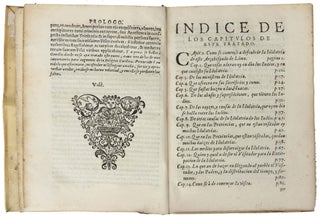

4to., (8) ff., 142 (ie 137) pp., (3) ff. Elaborate woodcut tailpiece on fol. **3v. With pastedowns and endleaves from a contemporary 4to liturgical service book printed in red and black. Bound in contemporary flexible vellum. Early ownership inscription of the second Jesuit college in the Americas, “El Collegio de S. P[edr]o y S. Pablo” on title page, and personal ownership inscription in an early hand of a Jesuit father, Padre Diego de Lacios [?] on the front cover. Vellum somewhat shrunken due to age, exposing margin of a few leaves to minor soiling: an extremely crisp copy, excellent. A fine and very genuine copy of the rare first edition of Pablo José de Arriaga’s meticulous account of the Indians of Peru at the turn of the 17th century. Intended as a manual to help clerics identify and eradicate native “superstitions”, the work is filled with minute details describing indigenous Andean ceremonies, medicines, and beliefs. Thanks to the all too effective execution of Arriaga’s duties, the Extirpacion de la Idolatria del Piru ironically remains the canonical source for much ethnographic and anthropological information on the very cultures he was trying to eradicate. Recorded by an eyewitness on the eve of the final wave of cultural obliteration campaigns against Incan and pre-Incan civilizations in the 17th century, Arriaga’s account is one of the earliest ethnographic records of post-Conquest Peru and an essential source for the historical reconstruction of now-lost Peruvian cultures. “In spite of its brutality, the book is a rich trove of Andean ethnography.” (JCB, “Sources of Peru”) Because of their ‘simplicity and poor understanding’ and their all too recent introduction to the Christian faith, the native peoples of the New World were not subject to the authority of the Holy Inquisition. The task of stamping out heresy instead fell to independent contractors – local bishops and religious leaders – who established a system in Peru modeled in essence on the Inquisition, but subject to far less regulation. (cf. Griffiths, “The Inquisitorial Model and the Repression of Andean Religion in Seventeenth-Century Peru”). Arriving from Spain and distressed to find native heresies thriving after one hundred years of evangelization, figures such as the Archbishop of Lima Bartolomé Lobo Guerrero, the Spanish Viceroy Francisco de Borja, and the Jesuit Provincial Pablo José de Arriaga all spearheaded vicious and concerted campaigns during the early 17th century to eradicate all traces of native religion and superstition. Only Arriaga, however, produced a written record of his work —Extirpation of Idolatry in Peru (1621). Compiled as a catalogue of all the heresies encountered by Arriaga in his fight against native religions, the Extirpacion chronicles Arriaga’s own experiences with Incan and indigenous Andean customs in order to assist others in recognizing these signs of idolatry. Later ecclesiastical leaders, such as Archbishop of Lima Pedro de Villagomes, would rely extensively on Arriaga’s detailed ethnographic descriptions in their own extirpation directives, cementing the work’s status as a classic source within the history and historiography of Colonial Peru and of its extirpation campaigns.[i] As a manual for others engaged in the ‘Extirpacion’, Arriaga’s work is organized into helpful chapters: “How to begin to uncover idolatry”, “What things the Indians venerate, and what their Idolatry consists of”, “What and how they offer sacrifices”, etc. Directions are given for a kind of protocol for such visits: on the first day, one must seek the assistance of the Cacique (local native leader); on the second day one reads out to the village proclamations against idolatry and sorcery (“it is especially important to explain that those who denounce others will be pardoned…”); and by the 12th day one should be ready to leave… “It is very good to carry in your hand some pieces of bread, or something similar, to give to the Indians you encounter” ... (81) Arriaga’s account is especially valuable for its detailed observations on contemporary indigenous medicine, including the use of coca, which Arriaga describes as “a universal offering to all huacas [idols], for all occasions (25)”. Coca remains ubiquitous in modern Peru (particularly as an herbal remedy for altitude sickness); yet, even before its notorious link to cocaine, the plant has been scrutinized and vilified since the colonial era for its use amongst indigenous Andeans.[ii] Arriaga exemplifies this concern about native botanical materia medica. Many sorcerers, he contends, are ambicamayos, or experts in the use of herbal medicines (34); but others are apparently expert only in the use of poisons, which they use to kill their enemies (38-9). And on page 71 he notes that the practice of the Spanish priests and officials conspiring to sell large amounts of liquors to the Indians for ‘medicinal purposes’ is becoming widespread. The Extirpation also contains extensive references to chicha, an Andean alcoholic drink still produced by traditional means and widely consumed today.[iii] Arriaga declares chicha to be “the principal offering, the best, and the biggest part of Indian sacrifice” (24). He details myriad uses of the corn-based beverage, from healing remedies like bathing the sick with chicha to wash away illness (51), to shamanistic rites, questioning “sorcerers” if the madness they claimed to experience when conversing with the huacas was from drinking chicha, or if it was the devil’s work (91). The text also recounts how sorcerers would combine chicha with the powder of another sacred botanical—the hallucinogenic “espingo[iv]”, causing them to “become crazed” during huaca ritual worship (24). Modern ethnobotanists have verified that combining a hallucinogen with alcohol heightens the experience of psychoactive substances and confirmed espingo is a neurostimulant—the plant even causes bulging eyes that may have contributed to Arriaga’s “crazed” impression.”[v] Archaeologists have definitive evidence that, since the Moche period (c. 100-700CE), the psychotropic fruit has been used in native rituals alongside psychedelics like the San Pedro cactus (from which mescaline is derived)[vi] and in traditional Andean medicine that, despite Arriaga’s best efforts, continue to this day. In modern Peruvian shamanistic healthcare, an espingo “plant diet” can even be used to prepare one’s body for a spiritual, psychedelic ayahuasca ceremony.[vii] Arriaga depicts espingo as a “dry small fruit, round like an almond, with a very strong odor, although not very good”, and notes its medicinal application for hemorrhage and stomach pains (26). His description of this illusive fruit is still a key source for modern research in ethnobotany and ethnomedicine, along with burgeoning research into the therapeutic application of psychedelics for treatment-resistant depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and more.[viii] Espingo is also currently used to treat epilepsy and susto (disorder akin to shock) in traditional Andean medicine, and has documented anti-coagulant and analgesic properties, as well as neurological effects that are currently under pharmacological review.[ix] Arriaga concludes his comprehensive report with a set of “Regulations to Be Left by the Visitor in the Towns as a Remedy for the Extirpation of Idolatry”. In addition to prohibitions against dancing and ceremonial sacrifices, he notably singles out the practice of native medicine as posing a great danger to recent converts. Arriaga views Indian medical practitioners as one of the main causes of idolatry – in treating their victims, with occasional success, these sorcerer-healers only encourage the idolatrous superstitions upon which most of their medicine is based (171). Interestingly, however, Arriaga also instructs priests to examine very carefully the healing methods of these native practitioners, “in order to get rid of what is superstitious and evil therein, and to profit by what is good, for example their knowledge and use of certain herbs and other simples” (99). Such attention to detail is what makes The Extirpation of Idolatry in Peru an unparalleled ethnographic and historical source on both pre-colonial Andean indigenous practices and colonial European attempts to eradicate them in the name of Christianity, as well as the complex, often brutal, process of acculturation and conversion in the face of native cultural persistence. Arriaga, once dubbed the “Cicero of Eloquence and Poetry’s Vergil” for his writing[x], was a contemporary of Incan chroniclers Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, whose Comentarios Reales de los Incas (1609) Arriaga mentions on page 37, and Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala, who completed his Nueva Corónica y Buen Gobierno in 1615—only six years before Arriaga’s work would be published. The Extirpation therefore forms a fascinating triangulation of perspectives on Incan and Andean culture in the early seventeenth century, and remains a seminal text in the history of Peru and colonial Latin America, as well as an invaluable source across a range of disciplines, from archaeology to ethnobotany to modern indigenous religion. A sought-after Americanum, the Extirpacion de la Idolatria del Piru has not appeared at Anglo-American auction in more than half a century. With Arriaga’s untimely death in 1622, his work was not re-published until 1910, making early modern editions “incredibly rare.”[xi] The present copy is in an unusually fine contemporary state, bearing an early exlibris of the missionary training College of San Pedro y San Pablo in Mexico City where, presumably, it was used to equip missionaries before heading into the field. No copy has appeared at Anglo-American auction in the last 50 years. * Sabin 2106; Adventures in Americana, 82; Palau I, 119; not in Church. Cf also Medina, La Imprenta en Lima, Vol 1 no. 92 (devoting 77 pages to this book); The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas, p. 850; Dorsey, A Bibliography of the Anthropology of Peru, p. 66 (“relates native religious beliefs and practices in minute detail”); and Mills’ monograph, Idolatry and Its Enemies: Colonial Andean Religion and Extirpation, 1640-1750 (Princeton University Press, 1997). This description is property of Martayan Lan Rare Books [i] Carlos A. Romero (ed). La Extirpación de la idolatría en el Perú, (Sanmartí y ca, 1920): xiv. [ii] J.P. Hafso, “Indigenous Identity and the Coca Leaf: Attitudes Towards the Coca Leaf in the mid-sixteenth century to the late seventeenth century in Colonial Peru” Constellations 10, n.2 (2019): 2-6. [iii] Frances Hayashida, “Chicha Histories: Pre-Hispanic Brewing in the Andes and the Use of Ethnographic and Historical Analogues,” in Drink, Power, and Society in the Andes (Gainsville: Florida Scholarship Online, 2011): 232-233. [iv] In present day, also known as ishpingo, ispinku, yspincu, or ispincu. [v] María del R. Montoya Vera, “Multidisciplinary Study of Nectandra Sp. Seeds from Chimu Funerary Contexts at Huaca de la Luna, North Coast of Perú,” in P. Eeckhout & L. Owens (Eds.), Funerary Practices and Models in the Ancient Andes: The Return of the Living Dead (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015): 253-256. [vi] Montoya Vera, 238; F.J. Carod-Artal, C.B. Vázquez-Cabrera. Semillas psicoactivas sagradas y sacrificios rituales en la cultura Moche, Revista de Neurologia,44, n.1 ( January 2007): 43, 48. [vii] See plantaforma.org/estudio-dietas-hermanosis , nihuerao.com/index.php/medicine-plants [viii] Henry S. Wassén, “Was Espingo (Ispincu) of psychotropic and intoxicating importance for the Shamans in Peru?” Agents and Audiences: Agents and Audiences, ed. Agehananda Bharati, (New York: De Gruyter Mouton, 1976): 511-520. [ix] Rainer W. Bussmann, Ashley Glenn, & Douglas Sharon, “Healing the Body and Soul: Traditional Remedies for “Magical” Ailments, Nervous System and Psychosomatic Disorders in Northern Peru,” African Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology (September 2011): 614; E. Auditeau, et al. “Herbal Medicine Uses to Treat People with Epilepsy: A survey in Rural Communities of Northern Peru,” Journal of Ethnopharmacology (April 2018 ): Table 6; Montoya Vera, 255-6, 258. [x] Sabine MacCormack, Religion in the Andes: Vision and Imagination in Early Colonial Peru, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021): 384-385. [xi] Horacio H. Urteaga (ed). La Extirpación de la idolatría en el Perú, (Sanmartí y ca, 1920): vi-vii. *rarísima

Price: $98,500.00