Institutionum Geometricarum.

Small folio [32.5 x 20.5 cm], (4) ff., recto of last leaf blank, woodcut of man with lute on verso, 185 pp., (verso blank), (1) f. (printer’s device on verso, recto blank); folding extensions on P6 & Q1 as required by Mortimer. Bound in 18th-century calf over boards, spine with raised bands re-backed, later red morocco title label. Title dusty; occasional toning; small wormtrack through much of volume, generally in blank margin but occasionally grazing a partial letter or printed border on plates. Withal a fresh copy, very good.

[Bound with:]

DÜRER, Albrecht. De Urbibus, Arcibus, castellisque condendis, ac muniendis rationes aliquot, praesenti bellorum necessitati accomodatissimae ...

Paris, Christian Wechel, 1535. (40) ff., including 10 double-page/extended leaves as described by Mortimer.

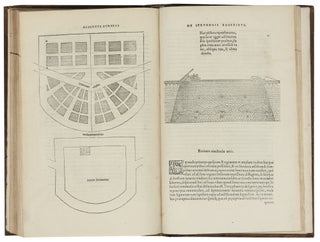

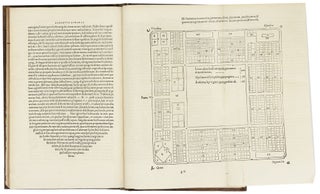

First Latin edition of Albrecht Dürer’s first book on the theory of art, the Unterweisung der Messung, bound with the De Urbibus, the first Latin edition of his treatise on fortification, a work considered to be “the first treatise dealing exclusively with this subject” (Krufft), and more broadly a landmark in urban planning, civic utopianism, and engineering. In the De Urbibus, Dürer treats not only theoretical aspects city construction, but also more practical details or architecture, such as preferred course patterns for ashlar masonry, the placement of chimneys, the proper spacing of fenestration, and the like.

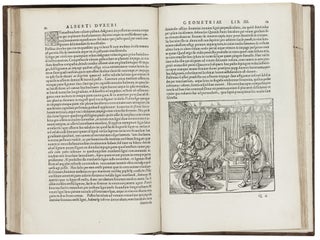

1) Illustrated by Dürer himself, the Institutionum Geometricarum outlines the artist’s theory of “the work of art as a natural object”, which became an accepted aesthetic dogma until the 19th century. Far more than the German original of 1525, this translation by the humanist Camerarius brought the treatise to the attention of the whole of Europe. As a theoretical statement by “the last major painter to be counted a significant geometer” (Kemp), the work is naturally of interest for applications in Dürer’s own oeuvre as well as for the history of perspective.

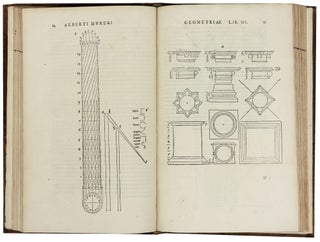

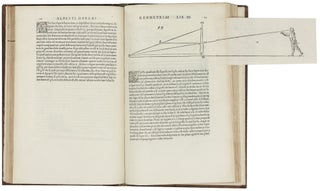

After his encounter with Luca Pacioli in Italy, Dürer became convinced of how close the links are between art and mathematics and devoted himself to the study of form through the resources offered by arithmetic and geometry. The result was the present work. In this work Dürer teaches the principles of perspective and explains the application of practical geometry to drawing and painting. It became a very influential text as its audience broadened from artists to architects, sculptors, and different craftsmen and was translated and reprinted several times.

Panofsky describes the treatise’s importance as three-fold: for the technical innovation in the construction of a perspective apparatus in which the eye of the observer is dispensed with entirely; for being the first literary document “in which a strictly representational problem received a strictly scientific treatment at the hands of a Northerner”; and for emphasizing that “perspective is not a technical discipline destined to remain subsidiary to painting or architecture, but an important branch of mathematics, capable of being developed into what is now known as general projective geometry” (Panofsky, p. 252).

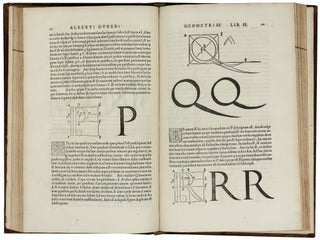

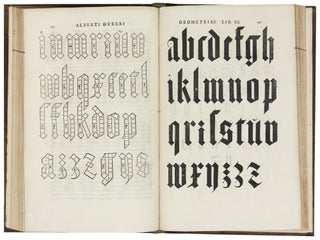

Book Three contains Dürer’s famous treatise on the just shaping of Roman capital letters and gothic or ‘Textur’ letters built up by means of small geometrical forms, a method original with Dürer. (This text was translated into English by R.T. Nichol for publication by the Grolier Club, Of the Just Shaping of Letters, New York, 1917.)

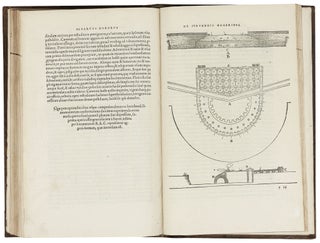

2) Inspired by the artist’s witnessing the siege of Hohenasperg in 1519 and by fear of the advancing Turkish armies, Krufft writes, De Urbibus “employs a dual approach. On the one hand Dürer develops various alternatives for the construction of bastions to defend existing cities; this is the contemporary aspect. At the heart of the treatise, he outlines a utopian city, in which the nature of fortification merely serves as a spur to the depiction of a social structure organized on the ground... Related trades are placed side by side; smiths are to be housed near foundries, etc. The town hall and the houses of the nobility are sited near the royal palace. The whole system of organization is hierarchical and functional. Dürer thinks of every function of the city, right down to the taverns” (Krufft, History of Architectural Theory, p. 110 ). Elsewhere Krufft suggests that Serlio employed the present treatise in book VI.

According to Mortimer, the woodblocks are close copies of the 1527 German original.

* (1)Mortimer, French I.182; Vagnetti E II.b7; Panofsky, The Life and Art of Albrecht Dürer, Chapter 8, “Dürer as a theorist of Art”, esp. 247-60; Kemp, The Science of Art, 53ff.; 2) Mortimer, French I.184; Fowler 113 (1527 German); Krufft, History of Architectural Theory, 110-111.

Price: $33,500.00