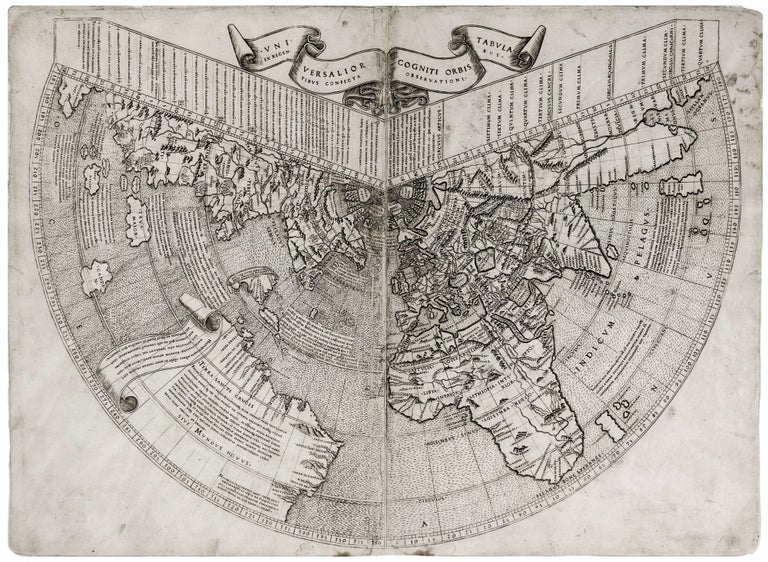

Universalior Cogniti Orbis Tabula. Ex Recentibus Confecta Observationi.

15 3/8 x 21 inches. Engraving on two joined sheets, mounted on early paper, as issued?. With full margins, restoration at points along centerfold with a few place names expertly facsimilized, but most affected surface non-geographic in nature; a crisp printing impression; very good overall. Very rare. One of the Holy Grails of map collecting--the earliest, acquirable map to show America. A very rare untrimmed example; nearly all copies we've seen have had at least some trimming. Suarez notes that the Ruysch was “the first published map made by an actual explorer of the New World.” It appeared the same year as the legendary Waldseemuller wall map of the world*, which is hailed as the first map to name “America.” However, the Ruysch is an overall more accurate work than Waldseemuller’s masterpiece, in its mapping of America as well as most of the rest of the world. The Ruysch map suggests by the sheer mass of South America it presents that indeed a new continent had been found in the Western Ocean. Thus, it represents the first cartographic support of Amerigo Vespucci’s Mundus Novus, published in 1504, and indeed seems to have been directly informed by the pamphlet. So, in a sense, the Ruysch can be viewed as a cartographic endorsement of the honor conferred on Vespucci in the naming of the New World after him. While both the 1506 Contarini (the only, earlier printed map to show America) and the Ruysch apply Cabral’s name for South America (“Terras Crucis” and “Terra Sancte Crucis” respectively) only Ruysch uses Vespucci’s term “Mundus Novus” “the first reference to a ‘new world’ on a printed map” -- Suarez. Overall, the Ruysch is a boldly original work. In spite of its Ptolemaic projection, Ruysch systematically broke with Ptolemaic tradition in virtually every area it was possible, doing so with the benefit of remarkably fresh information. The map shows a clearly recognizable South America with twenty-eight place names along the coast, including “R.DE.BRASI.L,” the first use of that name to appear on a printed map. The first land in Brazil spotted by Cabral, “MŌTE PASQVALE” is illustrated and named. Newfoundland (“TERRA NOVA” on the map) is detailed and includes seven place names along the coast. It is possible that some of these details were the result of direct observation by Ruysch himself. In a commentary in the 1508 Ptolemaic atlas in which this map appeared, it is said of Ruysch that he “’…sailed from England westward…bearing a little northward, and observed many islands.’” In the Ruysch map, we witness the intellectual struggle of a talented geographer responding to the onrush of new information, attempting to integrate it into an imperfect template. Ruysch’s mapping of newly discovered areas reveals that he wrestled with the question as to whether they were part of Asia or a new continent altogether. Very telling in this regard is a note near Hispaniola (“Spagnola”), in which Ruysch confesses that he does not know for sure where to locate Japan but concludes that ‘Spagnola’ must be the Japan (“Sipangu”) as described by Marco Polo. Also, Newfoundland (“Terra Nova”) is appended along with Greenland to the Asian continent. In this area is also “In[sulas] Baccalauras,” one of the first references on a map to the cod fishing industry. Shirley points out that “Ruysch’s map is the first to show many parts of Asia in the light of the latest Portuguese discoveries.” Ruysch even notes a Portuguese voyage to East India dated the very year of the map’s publication. For the first time on a map, India approximates its actual shape, and both Madagascar and Sri Lanka have been adjusted to correspond more closely to reality. However, Ruysch compromised with tradition by still including Taprobana, the erstwhile, greatly inflated Sri Lanka, but moved it away from India. A factor that speaks persuasively to the independence of Ruysch’s sources is how different this map is from the Contarini-Rosselli map. There are superficial similarities: Both mapmakers used Ptolemy’s conic projection, and both showed significant open water between the Caribbean and North America. In struggling to reconcile Ptolemy’s notion of the size of the globe with the evidence presented by the new discoveries in the Western Hemisphere, both mapmakers underestimate the distance between Europe’s western shores and Asia’s eastern reaches, to the point of conflating Newfoundland with Asia. Both maps reveal confusion with regard to the location of Japan: As mentioned, Ruysch postulates that Marco Polo’s Sipangu might be the island of Hispaniola, while Contarini puts Japan itself close to Cuba. But overall, Contarini’s essentially Ptolemaic geography and Ruysch’s reliance upon modern exploration result in very different maps. The Ruysch map is of considerable and documented rarity. McGuirk’s census uncovered 63 examples of the map. He estimated, however, the total number of extant examples is more likely in area of 100, still a relatively small number. Of the examples located by McGuirk, about three quarters of them were in institutional collections. Thus, only about 25 examples of the map are in private collections and could ever conceivably change hands. This map appeared in some copies of the 1507 Rome edition of Ptolemy’s Geographia, but it must have been a late addition to this edition, as it does not even appear in the table of contents. Most extant examples of the map appeared in the 1508 edition of the atlas. This example of the map is in the fifth state; sixty per cent of the examples surveyed by McGuirk were of this state. *The Waldseemuller map, known in a single example, was recently acquired by the Library of Congress in 2003 for ten million dollars. Only one other printed map precedes the both the Waldseemuller and Ruysch maps in showing America—the Contarini-Rosselli (Shirley 24) of 1506-- but this map is known in a single example (now in the British Library).

* Shirley 25; McGuirk, D. L. Ruysch World Map Census; Fite & Freeman 9; Nordenskiold, pp. 63-7; Suarez, Shedding the Veil, no. 12.